Feline Diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus is defined as an absolute or relative deficiency of the hormone insulin. Insulin is synthesised and released from beta cells in the pancreatic islets. Insulin assists with cellular uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into the cells of the body to be used for energy. This causes a hypoglycaemic effect. Within cells, insulin promotes anabolism by stimulating the production of glycogen, fatty acids and proteins, and counters catabolic events to reduce gluconeogenesis and inhibit fat and glycogen breakdown.

Insulin lowers blood glucose, whereas opposing hormones, including glucagon, cortisol, progesterone, adrenaline, thyroid hormone, and growth hormone, increase blood glucose. It’s important to consider these counterregulatory hormones, because changes in their blood concentrations interfere with the action of insulin. Changes in the concentrations of these hormones result from natural physiological conditions, disease states or drug administration.

When blood insulin concentrations are insufficient, the level of blood glucose increases, the kidneys become overwhelmed and glucose spills into the urine. The osmotic action of glucose leads to polyuria and, as a result of fluid loss, polydipsia.

In the absence of sufficient insulin, cats with diabetes will switch from glucose to fat metabolism for cellular energy, leading to significant weight loss and polyphagia. While this is initially beneficial, fat metabolism in undiagnosed or untreated cats typically causes a deterioration in health and progresses to ketoacidosis and, without treatment, ultimately to death.

The basic aims of diabetic monitoring are the determination of the right diabetic management strategy and thus establish a good quality of life. The key clinical signs of hyperglycaemia (polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia and weight loss) can easily be monitored at home and changes, suggesting an increase in blood glucose levels, can be picked up by cat owners and reported to their vet. This will help to manage any instability early and reduce the risk of diabetic keto-acidosis developing. Remember that hypoglycaemia is a rapid onset condition presenting with significant behavioural changes and must be treated immediately.

Diabetes mellitus is not related to diabetes insipidus, an extremely rare condition in cats that occurs when the kidneys are unable to regulate fluids in the body. Diabetes insipidus is characterised by a deficiency or inadequate response to vasopressin.

Disease prevalence and risk factors

Estimates of the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in cats is estimated at 1 in 200 cats1.The diagnosis is often preceded or accompanied by obesity. Diabetes is also more common in middle to older-aged cats. Neutered male cats are at greater risk than female cats.

Treatment factors

Determining an effective treatment regime for cats with diabetes can be challenging. Factors that affect the type of treatment and its success include:

- The severity of pancreatic beta cell loss

- The responsiveness of tissues to insulin

- The presence or absence of glucose toxicity

- Problems with the absorption and duration of action of exogenously administered insulin

- Presence of concurrent disease

- Evidence of ketoacidosis, diabetic ketonuria.

For some cats, oral medication with a SGLT-2 inhibitor may be considered, however for many cases insulin treatment will prove necessary. Additional monitoring tailored to the chosen approach will be needed depending on individual circumstances, dietary adjustments and weight management may also prove helpful. Advice on this site is primarily tailored towards cats being treated with Caninsulin.

Prognosis

In general, the prognosis for cats with diabetes is very good, especially with early diagnosis and proper therapy. Additional factors that affect the prognosis for cats include:

- Owner commitment to disease management

- Presence and severity of concurrent disorders (e.g. pancreatitis, acromegaly)

- Avoidance of chronic complications

The most common chronic complication of diabetes in cats is the development of peripheral neuropathy, which is exhibited by weakness in the hind legs. Diligent control of hyperglycaemia can potentially reverse the clinical signs of neuropathy, but it can take several months and may reoccur.

Open communication between you and your client is extremely important. Encouraging and supporting pet owners helps ensure their motivation and compliance with management protocols. A full understanding of the disease will help pet owners know how to achieve and maintain good stability in their diabetic cats. The clinical team has an important role to provide detailed client education, instruction and encouragement.

-

Classification

Diabetes classification in felines

Several classification systems have been used to describe diabetes mellitus. A human classification system revised in 1997 divides the disease into three types: Type 1 (previously insulin-dependent or juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus), Type 2 (previously non–insulin-dependent or adult-onset diabetes mellitus), and other specific types of diabetes mellitus (previously secondary or Type 3 diabetes mellitus).

Cats with diabetes that have an absolute deficiency of insulin are categorised as having type 1 or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Cats with Type 1 diabetes are thought to have a genetic predisposition combined with immunologic destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas2.

In comparison, felines that have the capability to still produce some insulin, but have a relative deficiency due to insulin resistance or other dysfunction, are classified as having type 2 or non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). Type 2 increased insulin production or increased insulin resistance is linked to genetic predisposition, obesity and certain medications. Some cats can be managed with dietary changes but, like dogs, the majority of cats with diabetes also need to receive insulin to maintain adequate regulation.

Feline patients with diabetes can fall under the type 1 (IDDM) or type 2 (NIDDM) classification. Initially, cats generally develop type 2 diabetes mellitus, but by the time the disease is diagnosed by a vet, it may have progressed to type 1, and the cat is dependent on exogenous insulin.

-

Aetiology

Primary causes of feline diabetes

There appears to be very little gender predisposition associated with diabetes in cats, although it is slightly more common in males than females7,8. As with dogs, the onset of diabetes in cats occurs most often in middle age.

The main metabolic characteristics of diabetes mellitus in cats are impaired insulin secretion and resistance to the action of insulin in its target tissues. A common histologic finding in diabetic cats is deposition of amyloid in pancreatic islets, associated with increased amylin production3. Selective infiltration of islets with amyloid, glycogen, and collagen leads to destruction of beta islet cells – in chronic cases, the islets become difficult to find.

Obesity, and pancreatitis are common findings contributing to insulin resistance in diabetic cats and so need to be managed carefully.

Obesity: The number of cats suffering from obesity is growing at a rapid rate – yet it is a condition that can easily be controlled by pet owners, with help from their veterinary surgeon. In obese cats, lipids are preferentially deposited in muscle tissue, causing the insulin sensitivity of tissue receptors to decrease, leading to a greater demand for insulin, which eventually results in the exhaustion of the islets of Langerhans4,5,6.

Pancreatitis: Chronic, relapsing pancreatitis with progressive loss of both exocrine and endocrine cells, and their replacement by fibrous connective tissue, results in diabetes mellitus. The pancreas becomes firm and multinodular and often contains scattered areas of haemorrhage and necrosis. As the disease progresses, a thin, fibrous band of tissue near the duodenum and stomach may be all that remains of the pancreas.

Secondary causes of feline diabetes

There are many pathogenic mechanisms responsible for decreased insulin production and secretion, but they are usually related to destruction of islet cells. Diabetes mellitus in cats can be secondary to severe inflammation or neoplasia of exocrine pancreatic tissue, which leads to loss of islet function. In these cases, diabetes is also complicated by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Diabetes mellitus can also occur when there is overproduction of counteracting hormones, for example in cats with acromegaly (hypersomatotropism) or hyperadrenocorticism or where cats have been given exogenous corticosteroids for long periods of time.

Acromegaly, or hypersomatotropism, in cats is caused by a growth hormone–secreting tumour of the anterior pituitary. In cats, these tumours grow slowly and may be present for a long time before clinical signs appear. Clinical signs of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus are often the first sign of acromegaly in cats and this condition should be ruled out during the initial diagnostic work-up of cats presented with poor diabetic regulation. It is not advised to test for acromegaly in the first two weeks of insulin administration, as the laboratory tests rely on reasonable insulin levels to be accurate.

Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing's Disease) or the administration of exogenous corticosteroids stimulates gluconeogenesis. This leads to an increase in blood glucose concentrations and therefore insulin production. Eventually the islet cells become exhausted and diabetes mellitus results.

In addition, stress and the administration of progestogens may increase the severity of clinical signs.

-

Glucose Toxicity & Hypoglycaemia

Glucose toxicity

Glucose toxicity occurs when insulin secretion is reduced by prolonged hyperglycaemia. Prolonged hyperglycaemia and diabetes mellitus can occur following the long-term, high-dose use of glucocorticosteroids or exogenous progestogens.

Progestogens have an antagonist effect on insulin, as they can lead to excess production of growth hormone and have an affinity for glucocorticosteroid receptors.

Hypoglycaemia in feline diabetes

Hypoglycaemia occurs when the blood glucose level drops to 3 mmol/L or less. Hypoglycaemia may be triggered by:

- Excessive dosage of insulin

- Overlapping insulin dosages

- Loss of appetite

- Vomiting

- Excessive exercise

This serious, and potentially fatal, condition can occur at any stage, even after stabilisation has been achieved. In some instances, no particular trigger is identified.

Clinical signs of feline hypoglycaemia

The clinical signs of hypoglycaemia that cat owners should be able to recognise are (in order of severity):

- Hunger

- Restlessness

- Shivering

- Incoordination

- Disorientation

- Convulsions and seizures

- Coma

It’s important to alert your cat-owning clients that early signs of hypoglycaemia may be subtle. Also, some cats will simply become very quiet and inappetant.

Coach your clients to watch for abnormal behaviours associated with hypoglycaemia.

Emergency treatment of hypoglycaemia

- Immediate oral administration of glucose solution or honey (1 g per kg body weight). Animals that are collapsed should not have large volumes of fluid forced into their mouths as this may result in aspiration pneumonia: here it is preferable to rub a small amount of the glucose solution or honey onto the animal’s gums or under its tongue.

- Intravenous dextrose solution (5%–10%) can be administered to effect in severe cases or, if oral therapy has been ineffective, add 120–300 ml of 50% dextrose solution to 1 L bag of fluids.

Following the successful emergency administration of oral glucose, offer small amounts of food at intervals of 1 to 2 hours until the effects of the insulin overdose have been counteracted.

Alert your cat owners that hypoglycaemia can be fatal to their pet and make sure they keep a glucose source, such as honey, on hand. Instruct your cat owners to rub honey into the cat’s gums and call the vet surgery immediately if they suspect hypoglycaemia. Remind clients never to force liquids or food on an animal that is unable to swallow.

If the insulin dose is too high, reduce it by at least 10%. It may be necessary to develop a blood glucose curve to appropriately adjust the insulin dose.

It is worth noting that hypoglycaemia may be the first sign that a cat is going into remission (especially if the cat’s weight has normalised, or concurrent diseases are being well managed) so it is important to keep monitoring at regular intervals to prevent further episodes of hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis

-

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of feline diabetes mellitus

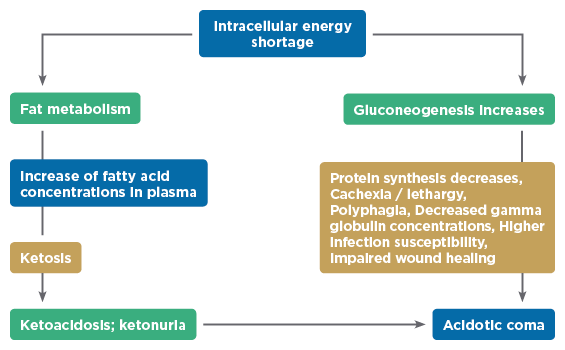

The insulin deficiency that occurs with diabetes impairs the uptake of glucose by cells, resulting in a great paradox: simultaneous extracellular hyperglycaemia (elevated blood glucose) and intracellular glucose deficiency.

To compensate for the glucose deficiency, gluconeogenesis occurs. This process stimulates the use of amino acids for glucose production, so there is a decrease in protein synthesis, subsequent weight loss and an increased risk of infections as a result of antibody loss.

The excess glucose produced accumulates in the blood, causing hyperglycaemia. Small glucose molecules are freely filtered through the glomerulus in the kidney. In normal cats, the renal tubules will reabsorb the filtered glucose. However, if the blood glucose rises above the renal threshold of approximately 12 to 16 mmol/L in cats, these tubular reabsorption mechanisms are overwhelmed, and glucose appears in the urine.

Glucose exerts an osmotic diuretic effect that leads to polyuria. To compensate, the cat experiences excessive thirst and polydipsia. Furthermore, the concentration of glucose in the bloodstream exerts an osmotic pressure and pulls fluid out of cells, resulting in cell dehydration. Without medical intervention, hyperglycaemic coma and death can occur.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the consequences of the deadly paradox caused by diabetes:

The pathogenesis of diabetes and resulting clinical signs of polyuria and polydipsia, alongside polyphagia and weight loss, help owners easily detect that their cat’s diabetes may not be well controlled. It is likely that polyuria and polydipsia are the first signs to be noticed, although it may be more difficult to detect in cats that spend more time outside.

Caninsulin®40 IU/ml Suspension for Injection contains porcine insulin.POM-V

Further information is available from the SPC, datasheet or package leaflet.

Advice should be sought from the medicine prescriber.

Prescription decisions are for the person issuing the prescription alone.

Use Medicines Responsibly.

MSD Animal Health UK Limited, Walton Manor, Walton, Milton Keynes, MK7 7AJ, UK

Registered in England & Wales no. 946942

References

- O’Neill, D.G. Et al. (2016). Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus among 193,435 Cats Attending Primary-Care Veterinary Practices in England. J Vet Intern Med;30, p 964–972.

- Nelson RW, Reusch CE. Animal models of disease: classification and etiology of diabetes in dogs and cats. J Endocrinol 2014;222:T1-T9

- Webb CB and Falkowski L. Oxidative stress and innate immunity in feline patients with diabetes mellitus: the role of nutrition. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 271–276.

- Hoenig, M . Carbohydrate metabolism and pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus in dogs and cats. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2014; 121: 377–412.

- Hoenig, M, Thomaseth, K, Waldron, M. Insulin sensitivity, fat distribution, and adipocytokine response to different diets in lean and obese cats before and after weight loss. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007; 292: R227–R234.

- Appleton, DJ, Rand, JS, Sunvold, GD. Insulin sensitivity decreases with obesity, and lean cats with low insulin sensitivity are at greatest risk of glucose intolerance with weight gain. J Feline Med Surg 2001; 3: 211–228.

- Prahl A, Guptill L, Glickman NW, et al. Time trends and risk factors for diabetes mellitus in cats presented to veterinary teaching hospitals. J Feline Med Surg 2007;9:351– 358.

- Slingerland LI, Fazilova VV, Plantinga EA, et al. Indoor confinement and physical inactivity rather than the proportion of dry food are risk factors in the development of feline type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vet J 2009;179:247–253.